The Association for the Study of African American Life and History has proclaimed African Americans and Labor as the theme for this year’s celebration of Black History Month:

The 2025 Black History Month theme, African Americans and Labor, focuses on the various and profound ways that work and working of all kinds – free and unfree, skilled, and unskilled, vocational and voluntary – intersect with the collective experiences of Black people. Indeed, work is at the very center of much of Black history and culture. Be it the traditional agricultural labor of enslaved Africans that fed Low Country colonies, debates among Black educators on the importance of vocational training, self-help strategies and entrepreneurship in Black communities, or organized labor’s role in fighting both economic and social injustice, Black people’s work has been transformational throughout the U.S., Africa, and the Diaspora. The 2025 Black History Month theme, “African Americans and Labor,” sets out to highlight and celebrate the potent impact of this work.

I am celebrating the work of Moses Williams who was born into slavery in Philadelphia in August 1776.

Enslaved by Charles Willson Peale, Williams was a factotum at Peale’s Museum. He participated in the first paleontological expedition in the early republic. As a skilled taxidermist, Williams was instrumental in the reconstruction of Peale’s excavated mastodon.

Manumitted in 1802, Williams operated a physiognotrace (face-tracing) machine “every day and evening” at Peale’s Museum.

Working in anonymity, Williams became a master silhouette artist and contributed to the success of Peale’s Museum. In Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now, Asma Naeem observed:

Williams defied racial strictures by using his [hands] to make the portraits of hundreds of thousands of white individuals. The sight of Williams operating the physiognotrace at the Peale Museum on a daily basis, year after year, offered a consistent, if somewhat tepid, rebuke to the proslavery discourse of suppression and forcible restraining of black people – in effect, an undoing of the chained hands of the African in Josiah Wedgwood’s “Am I not a man and a brother?”… In no uncertain terms, Williams became less disenfranchised with the commercial viability of silhouettes, changing his position from being enslaved to buying his own home and marrying the white Peale family cook. … [Williams was] able to enjoy a success inextricably tied to the rising status of the silhouette as a domestic commodity and popular mode of representation.

Williams is the subject of countless scholarly articles. His silhouettes are on view at, among other places, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Portrait Gallery in the Second Bank of the United States, The Peale Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, and Thomas Jefferson’s Library at Monticello.

Williams was born one month after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. He was enslaved by “The Artist of the Revolution” Charles Willson Peale who, as a member of the Pennsylvania General Assembly, voted for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery Act of 1780.

Williams was the nation’s first Black museum professional. While working on the second floor of the building now known as Independence Hall, he excelled as a “cutter of profiles” and earned a place in history.

To recognize his impact on the Revolutionary era’s visual culture, I have nominated Moses Williams for a Pennsylvania historical marker. If the nomination is approved, Williams’ marker will be dedicated in 2026, which is the 250th anniversary of both Williams’ birth and the founding of the nation.

Moses Williams will not be celebrated by President Trump’s Task Force 250, but we the people will say his name.

In the meantime, I will investigate what happened to Williams’ remains.

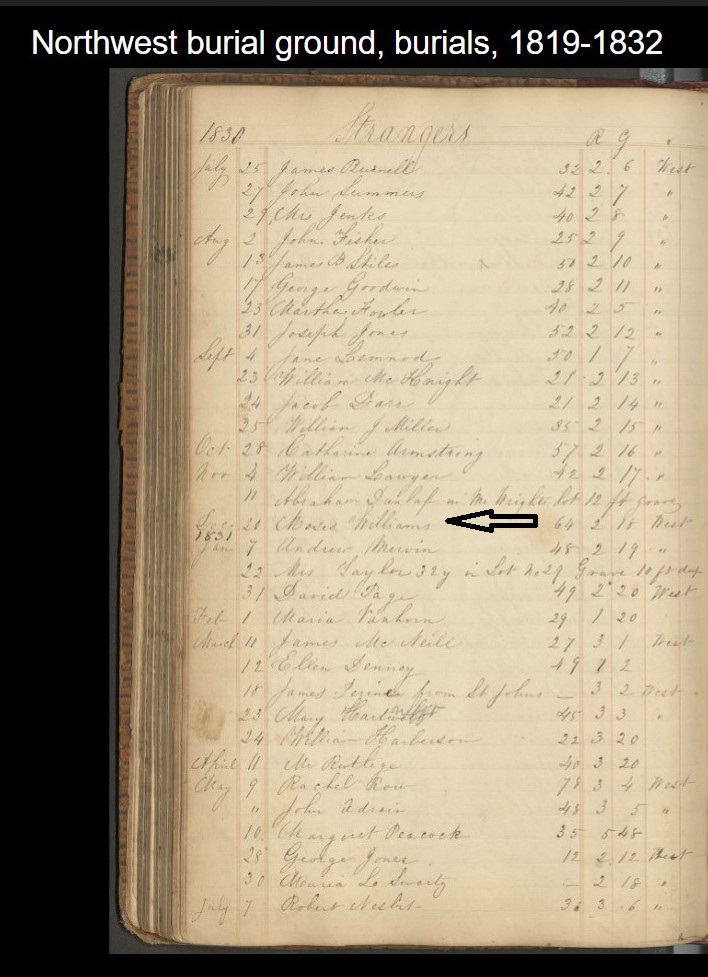

Williams joined the ancestors on December 18, 1830. He was interred at Northwest Burial Ground on December 20, 1830.

Northwest Burial Ground was located in North Philadelphia. Between 1860 and 1875, the burial ground closed, the bodies disinterred, and the land developed for a church. So where was Williams reinterred? Is his gravesite marked?

For updates, send your name and email address to phillyjazzapp@gmail.com.